There's a perverse logic to Indian residential schools. Settlers' farming methods are incompatible with hunting tradition as farming requires that animals be kept out of the fields. There's a need to fence land, which means that it was no longer available to wild animals or hunters, and it was probably inevitable that disagreements would develop between settler communities and First Nations over land use. The American Indian Wars of the late 18th and 19th centuries highlighted these conflicts. For close to 100 years, the Canadian governing elite had seen the effects of these wars.

If you are going to take over land, why not do it through those who are most vulnerable and unable to defend it? At the request of Sir John A. Macdonald, Conservative MP Nicholas Flood Davin wrote a report on residential schools. He had toured schools that had been designed to assimilate American Indian children. We can credit these two politicians, Sir John A. and Davin, for this brilliant strategy -- first send First Nations and Metis children to industrial (residential) schools to assimilate them to a different way of life and then claim their traditional lands while avoiding the cost of war. I am no expert and I know I am over-simplifying the situation but the logic of this rationale seems obvious.

The stories of the survivors of residential schools are truly heart-wrenching -- beatings, physical and psychological torture, sexual abuse, starvation, general deprivation, disease, loss of language and culture, loss of love and parenting skills, and soul-numbing loneliness. According to CBC's The National, during the early years of residential schools, 50% of the children died. DIED! Perhaps the original intent hadn't been to wipe out aboriginal children, but how can it not be considered an act of genocide when the number of deaths in the schools became apparent and yet the programme continued?

Perhaps the term cultural genocide is a kindness that reduces the edge. June Callwood, a hero of mine, died eight years ago this spring. She called kindness her religion. I have also found kindness to be typical of the First Nations people I have come to know over the last few years.

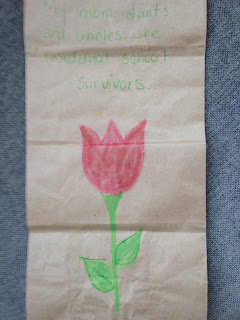

On Monday, I volunteered at the Commission's student activity day and I'm pleased to say that thousands of students participated. The lunches were packed in brown bags decorated with drawings made by First Nations children. It's one example of a simple act of kindness. My lunch bag said, "My mom, aunts and uncles are residential school survivors." I get teary each time I look at it. It moves me that survivors and their children made the effort to reach out to us through this very human gesture.

In an earlier post, A rabbit on the doorstep, I told the story of my mother's grandmother and her hardships in homesteading in Saskatchewan. It was based on a history written by my great-grandmother that recounted how the kindness of nearby First Nations people kept her family alive. But my great-grandmother's story was likely not unusual. Perhaps you are here today because of the generosity of your ancestors' aboriginal neighbours?

My father's side is of Irish descent. My grandfather carried coal to wealthier homes on Montreal's Mount Royal to help support his younger siblings. And my father told me about signs in Montreal restaurant windows that stated, "No dogs or Irish here." I'm sure many of you identify with my story; life wasn't easy for immigrant families who came to Canada, still they could make a living. Was it simply hard work that allowed my relatives and yours to prosper? Hard work was a part of it but they had worked hard in the old country too. What was different here?

The land on this side of the Atlantic was very fertile and not depleted by continuous cultivation. It had not been logged or mined and it was plentiful in resources. The wealth of this land gave our ancestors an edge. Much of it has not been ceded by treaty. Ethically perhaps even legally, it still belongs to the First Nations. Our relatives may not have played a direct role in creating residential schools or in taking First Nations lands but they profited unknowingly from the proceeds of crime. We have benefitted from this system of stolen land.

Unknowing no more! I wept in the safe, comfortable confines of my home as I watched Justice Murray Sinclair present the Commission's recommendations. I cannot choose to forget the pain I heard from residential school survivors. Reconciliation is not something we do to simply make amends for residential schools. It's a gift we give ourselves, our children and future generations. It's the opportunity to live together in common understanding and harmony. It's not only the right thing to do, it's simply smart to look toward a common future by acknowledging both the history of wrongdoing and the many kindnesses given to our ancestors in times past.

No comments:

Post a Comment